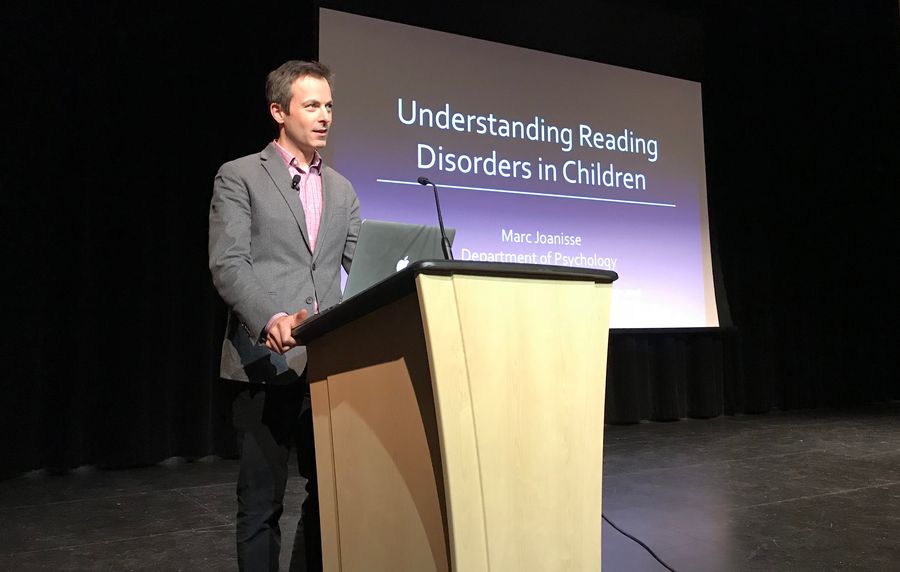

Q&A with Marc Joanisse: Understanding Reading Disorders in Children

On October 22, Professor Marc Joanisse from the Department of Psychology at Western spoke at the London Central Library on the topic of reading development and reading disorders in children. His work in this area, supported by BrainsCAN, focuses on language acquisition, language processing, computational models and how language is represented in the brain.

In this Q&A, Dr. Joanisse discusses the underlying problems of reading disorders and how they are identified in children.

Why is learning to read so hard?

Dr. Marc Joanisse: Reading can be hard to learn because it’s not just another form of spoken language. While we think humans evolved to use spoken language, learning to read involves adapting how we use existing brain regions meant for other purposes. Also, merely being engaged in an environment doesn’t teach children to read like it does if they were learning how to talk. Instead, children have to be taught to read, and the way we teach them has a profound impact on how they learn.

What do studies on reading disorders tell us about how children learn?

MJ: Studies show that the decoding approach is the best way to teach children to read. Decoding is sometimes called decomposition or phonics. It explicitly teaches children to associate letters with speech sounds (known as phonemes). This decoding process is important because it allows children to know what sounds go with certain letters. This is true for any word, not just a familiar one, and so decoding is key for helping children read new words.

There is a lot of research that suggests moving towards phonics and phonological awareness-based approaches for young readers has a positive impact for many children. By focusing on a decoding-based reading curriculum, like Ontario has done for the past 20 years, we have seen a big boost in reading scores among children.

What is dyslexia?

MJ: The classic definition of developmental dyslexia is the slow development in reading. Sometimes we will use the more general term "reading disability" instead of dyslexia to describe children who have difficulty reading, but the two terms mean the same thing. Affected children read very slowly and also produce many errors in the process. They mispronounce words because they’re not able to accurately learn how letters are associated with individual speech sounds. A reading disability is not associated with another cognitive disability and can occur in all languages. These children generally fall years behind in their reading progression if no intervention is offered.

How do I know if a child has a reading disability?

MJ: Children are typically diagnosed with a reading disability based on scoring significantly below average on reading tests. There is no universally agreed-upon cutoff score for how poorly a child needs to be reading. It all comes down to where you draw the line and if a child is below an expected level of achievement. This means that any child who is falling behind can potentially benefit from reading remediation programs, regardless of how significant their reading disability is. There is also good evidence indicating that children benefit from reading remediation programs even if they have other concurrent difficulties such as cognitive delays or ADHD. We should be careful not to exclude children from reading remediation programs just because they have other kinds of non-reading learning difficulties.

What are the myths associated with reading disabilities?

MJ: One myth is that reading difficulties are due to low intelligence or laziness. In fact, many children with reading difficulties score in the normal range or higher on cognitive measures such as IQ tests.

Another myth is that having a reading difficulty promotes "divergent thinking" or "creativity". Here again, we see no clear correlation between a reading disability and the tendency to be above average on other kinds of skills. This does not mean all children who are poor readers will fall behind on other abilities as well. However, it does mean that we cannot expect children with reading disabilities to automatically excel in other domains, and we need to provide the help they need with reading so they have the greatest chance of success as they grow older.

A third myth focuses on reversing letters as a way to identify a reading disability. People commonly associate dyslexia with writing or reading words backwards or upside down. Reversing letters, or forgetting which direction to write, is a part of normal development in nearly all children. At some points during reading development, children might forget which way to write or they reverse similar letters like d and b. These are typical patterns of normal development. A child with a reading disability might be more likely to commit these errors later into childhood, although this is not always the case and we should not use these types of errors to identify a reading disability.

Why do some children have reading disabilities?

MJ: The proposed cause of many reading disabilities is related to how children code the spoken form of language (phonology). These difficulties are sometimes identified using measures of phonological awareness, which require them to identify, analyze and manipulate phonemes in a word. Children with reading disabilities haven’t discovered that spoken words are broken up into individual phonemes, and because of this they have more difficulty associating those sounds with letters on the page.

How do we help children with reading disabilities?

MJ: Approaches to reading remediation in children with reading deficits should focus on identifying and improving their specific weaknesses. Reading remediation approaches that are the most effective appear to be phonics- and phonological-awareness based approaches, which try to reinforce phonological and decoding skills in children.

There are many phonics-based remediation programs that have been proven to be effective with children. Some of the most popular are:

What’s the current research in this area?

MJ: Our current research, supported by BrainsCAN, tests children before and after they’ve had reading remediation. We compared two sets of children – those who are getting reading remediation training programs through local schools, and those who aren’t. This research looks at how connections among brain regions change as a result of reading remediation. What we have found so far is that parts of the brain are becoming better connected as a result of children being exposed to, and participating in, a reading remediation program. The areas of the brain showing an improvement are involved in mapping the auditory aspects of sound with the articulatory parts of sounds. This research emphasizes how the brain processes letters and sounds together.

Why do some adolescents continue to have reading issues?

MJ: Students who are beginning middle school or even high school might still struggle with reading, even if they have received additional help learning to read individual words. These students can show specific difficulties understanding sentences or text. Often, their comprehension difficulties are because they’ve fallen behind in all aspects of reading, especially as they’ve progressed through the school years, and they may still need additional help to get them caught up. There is growing interest in researching how comprehension training, such as what is provided by the Empower Reading program, can help older readers.

What should parents and educators look for in a reading remediation program?

MJ: A good reading remediation program tends to emphasize the reading processes that we think are most likely to go wrong with children who have reading problems. The research suggests that the best way to help children learn to read is by focusing on phonological awareness and decoding.

Additional reading disability resources

For more information, please click on the links below.

London and area:

Learning Disabilities Association – London Region

Boys & Girls Club of London

London Public Library R.E.A.D. Program

Canada:

Empower Reading

Scottish Rite Learning Centres

International:

Lindamood-Bell

Orton-Gillingham

International Dyslexia Association

Dr. Marc Joanisse is a Professor in the Department of Psychology, a BrainsCAN-aligned researcher, and a Principal Investigator in the Brain and Mind Institute.