Thinking beyond the neuron

BrainsCAN research examines how extracellular components can control memory formation

How does the brain control what information becomes memories and can this be affected by diet and obesity?

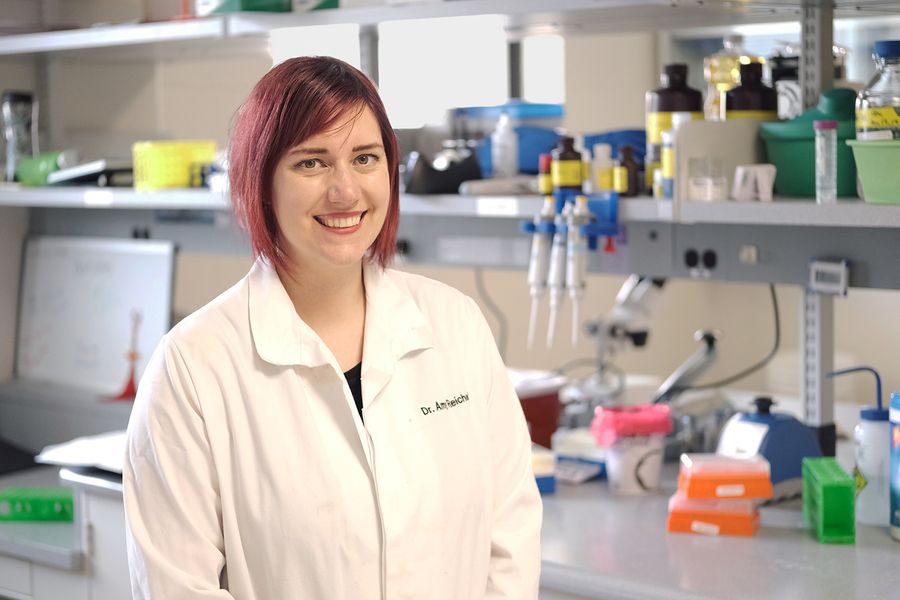

A new article from Western University published today in Trends in Neuroscience describes the role of perineuronal nets (PNNs) – structures that enmesh certain neurons in the brain – in protecting the neuron and regulating how often the brain turns experiences into memories. Dr. Amy Reichelt, a BrainsCAN Postdoctoral Fellow at Western, along with renowned Western neuroscientists and professors in the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Dr. Lisa Saksida and Dr. Tim Bussey describe PNNs, what effect they have on the brain and what happens when they’re not working.

“When you’re learning new things, you’re forming memories and making connections [synapses] between neurons in the brain,” said Reichelt, the study’s lead writer. “PNNs can either prevent you from learning new things by maintaining existing connections, or they can enable you to form these long-lasting neural pathways in the brain that are vital for behaviour.”

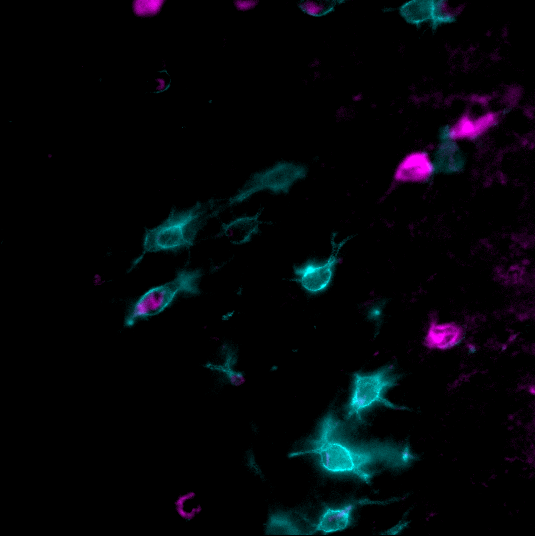

Structurally, PNNs form mesh-like webs around neurons in the brain. When working properly, PNNs have been shown to protect neurons and synapses from toxins by forming a physical barrier or a shield around the neuron. PNNs also control the plasticity of these neurons by regulating the stimuli that could influence them. However, if malfunctioning or nonexistent, neurons without PNNs might be influenced by all experiences, potentially resulting in memories of irrelevant information. This abnormal plasticity has been connected to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders including anxiety disorders and drug addiction.

Perineuronal nets (PNNs) seen here in a teal colour forming mesh-like webs around neurons in the brain (shown in pink).

“If you remove PNNs from the area of the brain that is critical for recognition memory the memories can last for much longer. This could be a way to overcome the cognitive deficits associated with Alzheimer’s disease,” said Reichelt who also worked with co-author Dr. Dominic Hare from the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health at the University of Melbourne. “The caveat is that increasing plasticity in the brain helps form lots of memories, but you’re also exposing your brain to damage because these PNNs protect your neurons.”

Reichelt’s work has shown that PNNs and the neurons they encase can be damaged by poor diets. Excessive consumption of junk foods that are high in saturated fats and refined sugars can cause toxic inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain resulting in cognitive decline and poor memory.

“If some neurons don’t have the PNNs protecting them they can be vulnerable to toxins,” said Reichelt. “The inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain caused by junk food diets could be affecting these neurons in particular.”

This shows that diet and lifestyle may have an impact on other elements of the brain like PNNs, and not just the neurons. Reichelt’s research also demonstrates that certain lifestyle factors, including exercise or environmental enrichment, might improve cognition by naturally modifying the PNNs.

“This research gives rise to ideas that potential therapies don’t have to be drugs that affect the firing of neurons in the brain – they could be lifestyle changes that affect the environment the neurons and synapses are contained within,” said Reichelt.

“What’s really exciting is that there’s more to the brain than neurons; we’re learning there are many factors that influence how our brain functions.”

BrainsCAN is Western University’s research initiative in cognitive and behavioural neuroscience that aims to transform the way brain diseases and disorders are understood, diagnosed and treated.