Amnesia and memory processing: Q&A with Dr. Stefan Köhler

Imagine suffering a traumatic brain injury that erases all memories of your personal past, or your ability to create new memories of your future. These are rare forms of memory loss that can greatly impact those who experience them, and alter their sense of who they are and how they live their lives.

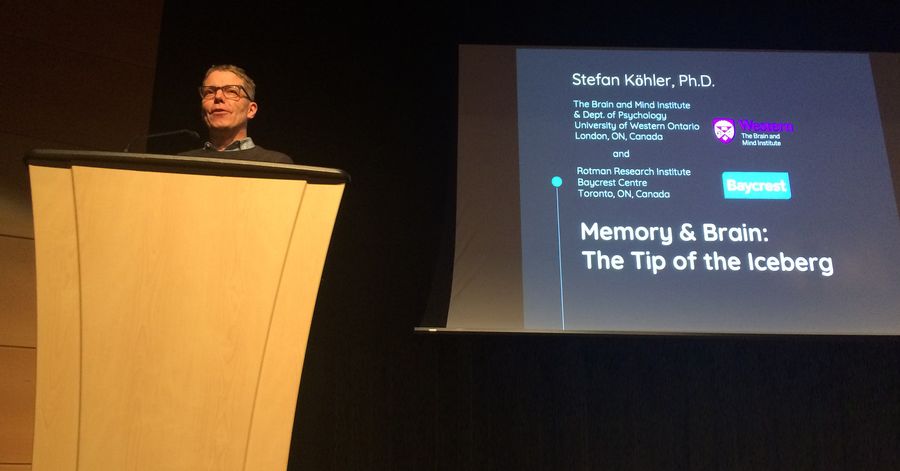

Dr. Stefan Köhler is the Chair of Cognitive, Developmental and Brain Sciences in the Department of Psychology at Western University who studies human memory and its disorders. His research focuses on how the brain forms, stores, and recovers memories. His work has also led him to examine brain injuries or other neurological diseases that can cause amnesia.

When you think of amnesia, you may think of Hollywood movies including 50 First Dates, The Bourne Identity, or Memento. Some of the features of amnesia captured in these movies reflect what scientists have learned about this condition over the past several decades.

Amnesia is memory loss caused by damage to areas of the brain that are essential for memory processing. Examining patients with amnesia has helped Dr. Köhler and other researchers learn how memory is processed in the brain, and what happens when this is impacted by a brain injury or neurological disease.

Earlier this year, Dr. Köhler spoke about memory and the brain at a London Public Library talk. This article is adapted from that talk.

What is anterograde amnesia?

Dr. Stefan Köhler: Scientists have learned a lot about human memory from systematically studying individuals with memory disorders. Henry Gustav Molaison, known for decades as HM, is one of the most extensively studied cases.

Henry suffered from anterograde amnesia, a memory disorder that reflects impairments in the ability to form new long-term memories of ongoing experiences. His case was first reported in the 1950’s by Canadian psychologist, Brenda Milner and an America neurosurgeon, Dr. William Beecher Scoville, who had conducted brain surgery on Henry in an attempt to control his severe epileptic seizures. A part of his brain that included a pair of structures known as the hippocampus was surgically removed to treat Henry’s epilepsy. This surgery resulted in the expected alleviation of seizures; however, the limited knowledge of the brain basis of memory at the time did not allow Scoville to predict the severe and lasting memory impairments that also resulted from this surgery. The act of cutting out his hippocampus meant that Henry would suffer from anterograde amnesia for the rest of his life.

Even after his surgery, Henry maintained his reasoning and language capabilities. For example, he could comfortably engage in meaningful conversation. However, as soon as information left his mind – like when he was distracted thinking about something else – he was unable to bring that information back. This inability to recover information once it has slipped the mind constitutes the core problem of anterograde amnesia in Henry and in other cases.

In everyday life, people with anterograde amnesia have difficulties recognizing new people and remembering their names. They often can’t find their way in their environment, and they can’t remember where they left things. They also find it difficult to keep track of what has happened already and what hasn’t. We all encounter memory problems of this sort here and there, but for someone with anterograde amnesia these problems are pervasive and of a completely different magnitude.

There are a number of neurological conditions that can produce such severe memory impairments. They can be caused by a traumatic brain injury, a viral infection to the brain, a lack of oxygen supply, or a long-lasting lack of vitamin B1. In the case of Henry, as mentioned, his anterograde amnesia was the outcome of brain surgery.

In the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, memory impairments can be similar to those in anterograde amnesia. Because Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, however, it also affects other cognitive functions in the long run.

What is retrograde amnesia?

SK: Several years ago, I worked with a patient named Kent Cochrane who had a very serious traumatic brain injury and severe amnesia after a motorcycle accident in his 30s. In addition to difficulties in forming new memories, Kent was diagnosed with retrograde amnesia, a condition characterized by loss of memory for information acquired before his injury.

Given the nature and extent of his brain damage, none of Kent’s memories from before his motorcycle accident survived – that is, he no longer had any specific episodic memories, or memories of past personally experienced events.

It is interesting to note that semantic memory, or knowledge of facts, was still preserved in Kent. This means that individuals with retrograde amnesia typically lose a sense of their very personal happenings, yet retain some knowledge of themselves. They can still tell you who they are, who their family is, and some other facts about themselves, but they cannot bring back to mind any moments of their past. For Kent, he could not bring back any specific personal experiences prior to or after his accident, including for example, an event as memorable as attending his brother’s wedding.

What is dissociative amnesia?

SK: Dissociative amnesia is a grave memory gap for a more circumscribed period of time. Such gaps involve an inability to recall specific information from this period, typically centered around events of a traumatic or stressful nature. They affect past personal experiences as well as personal identity. This kind of amnesia doesn’t exist endlessly – it typically lasts just days, sometimes weeks, or months. Afterwards, patients can recover and restore at least some of their memories of events and related knowledge.

Dissociative amnesia differs from retrograde amnesia in several ways. Unlike retrograde amnesia, it affects a restricted life period, it affects the sense of self in a pervasive manner, it is not permanent, and, perhaps most critically, it cannot be directly linked to the presence of a neurological condition.

We know that dissociative amnesia is not the result of brain damage to the hippocampus. In fact, it is difficult to point to any consistent brain damage, and some individuals with dissociative amnesia have, to our knowledge, no brain damage at all. This is why this type of memory disorder is sometimes also referred to as psychogenic amnesia – we cannot easily rule out that the individual willingly chooses not to revisit certain memories, or denies the presence of memories that are in fact there.

Can psychological trauma and brain injury lead to similar types of memory problems?

SK: This is a complex issue as it touches on deeper questions about the relationship between mind and brain. There is an increasing appreciation among scientists that severe psychological trauma can lead to changes in brain functioning, and that it also affects memory. Much of this insight has been gained from research on post-traumatic stress disorder (for example, in war veterans).

The nature and extent of changes in memory that will be present after psychological trauma versus brain injury differ significantly. In most cases, a review of clinical history, a neurological examination, and a careful assessment of the individual’s memory profile allow clinicians to distinguish between both conditions without difficulty. Overall, most clinicians and scientists agree that it’s important to think of psychological trauma and brain injury as separate things.

How does studying amnesia help researchers understand how the brain stores memories?

SK: Studying memory with scientific methods in amnesic patients such as Henry Gustav Molaison or Kent Cochrane has led to the understanding that brain mechanisms aren’t the same for all types of memory. Even specific types, like episodic memories, don’t just rely on a single brain structure. Studies conducted with brain imaging in neurotypical individuals confirm and extend what we’ve learned from research on amnesia, namely that memories are not stored in one part of the brain, they are distributed.

The laying down of memories, their storage, and their recovery engages many different brain regions, some of them acting as memory hubs. But these hubs interact in broader networks. That’s the new frontier of the science of memory – researchers are trying to understand the networks that are critical at each stage, and how their engagement changes as memories fade or become strengthened.

To understand the brain mechanisms that underlie human memory, there’s a lot more we need to do as scientists. Examining individuals who suffer from amnesia plays an important part in this enterprise. The outcome will provide us with insight that eventually also holds promise for the effective treatment of memory disorders.

---

Dr. Stefan Köhler speaking at the London Public Library event, Grey Matters – Conversations about Brain and Memory

Dr. Stefan Köhler is the Chair - Cognitive, Developmental and Brain Sciences in the Department of Psychology, Professor in the Faculty of Social Science, Principal Investigator in the Brain and Mind Institute, and Associate Scientist at Rotman Research Institute, Baycrest Centre.

What causes déjà vu? Read about Dr. Köhler’s discovery of memory and déjà vu.