Contact Information

Hassam Ansari

Communications Officer, BrainsCAN

Western University

hassam.ansari@uwo.ca

Behavioural research gets boost with first open-access database

December 17, 2019 - BrainsCAN Communications

Neuroscience researchers at Western University have developed the first open-access repository for raw data from mouse cognitive testing. Called MouseBytes, the database gives researchers a platform to share rodent cognition data using touchscreen cognitive testing with labs around the world. It is supported by Western’s BrainsCAN, and built on previous funding from the Weston Brain Institute.

A new paper published last week in the journal eLife describes how MouseBytes can enhance transparency, data sharing and reproducibility in research findings. By sharing research data and working collaboratively, researchers can use MouseBytes to gain an improved understanding of rodent cognition – and ultimately, discover insights into how the human brain works. The work involved expertise from Western researchers, along with researchers at other institutions including co-senior author, Boyer Winters from the University of Guelph.

“MouseBytes allows researchers to upload data to a repository where everyone has access,” said Marco Prado, co-senior author of the study and a Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry professor. “Open science ensures that by having increased availability of datasets, researchers can reuse, reinterpret and reanalyze data to find new avenues for research.”

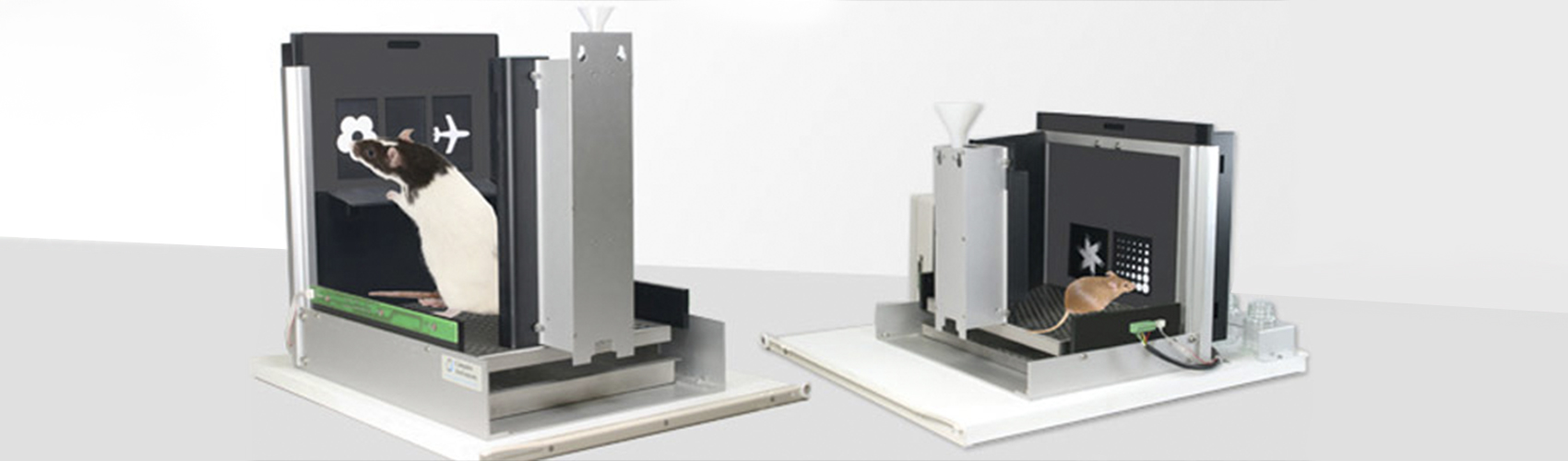

The development of MouseBytes was possible with touchscreen cognitive testing – a form of behavioural testing developed by Western researchers, Lisa Saksida and Tim Bussey. In the touchscreen testing environment, mice are trained to take part in cognitive tests by touching images on an iPad-like touchscreen – exactly like cognitive tests for humans. While the mouse is completing a task, researchers can track its neural activity.

The technology used at Western, aptly called Bussey-Saksida Touch Systems, was licensed to Campden Instruments when its inventors were still at the University of Cambridge. Many years of technically complex research and development has enabled other scientists to purchase them off-the-shelf, knowing they have been optimized and standardized. Any licensing income Saksida and Bussey receive is fully reinvested in further fine-tuning the systems, which are available to Western researchers through the BrainsCAN Rodent Cognition Core.

“The best thing about the touchscreen tasks is they are very similar and sometimes the same as tasks for humans,” said Flavio Beraldo, co-first author of the paper and Research Associate at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. “We can compare humans and mice side-by-side to see if they have the same response to a task.”

“Touchscreens can also be seen as an improvement over other methods to motivate behaviour,” added Bussey, senior author of the study and Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry professor. “Touchscreens achieve the same aim using strawberry milkshake, which mice love.”

The touchscreen system includes behavioural protocols controlled by a computer system, allowing increased standardization of research results. Since the systems are regulated, researchers can replicate tests completed at any of the over 300 labs around the world using the touchscreen method.

“By pairing a behavioural system, such as touchscreen cognitive testing, with MouseBytes, we’re able to start standardizing experiments that were previously not able to be standardized,” said Daniel Palmer, co-first author of the paper and postdoctoral associate at Robarts Research Institute. “This allows us to compare data sources that were previously not able to be compared.”

MouseBytes currently houses datasets from over 1,000 mice that can be reviewed, extracted and compared with other data collected from labs around the world. This large open-access database has enabled the development of new analytical tools allowing researchers to address questions that could not be answered using single datasets.

Researchers at Western are also making significant improvements in the behavioral assessment of mouse models and building a community of researchers by providing a way to share and standardize knowledge for touchscreen testing. MouseBytes is part of this initiative using the platform touchscreencognition.org, developed by researchers at Western with support from BrainsCAN, to disseminate knowledge and data, and train the next generation of researchers.

“Instead of dedicating lots of time and money to collect data from a test and do the analysis, researchers can go to MouseBytes first and extract these data,” said Sara Memar, co-first author of the study and BrainsCAN Neuroinformatics Specialist and Data Scientist. “They can get an idea of what’s going on in these data to better design their experimental research. It can accelerate the translation of research findings to clinical practice.”

An immediate benefit of MouseBytes is the potential for insights into current brain disease models. By comparing three different mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease in MouseBytes using touchscreen cognition tasks, the researchers were able to identify the mouse lines and tests most useful for the evaluation of cognition in these models. It also allowed acquisition of the largest dataset of cognitive performance for female mice. Currently, research is biased toward data from male mouse models, even though certain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, affect more women than men. The current repository was generated with an equal number of female and male mouse models.

“Even within the scope of the first three mouse lines we’ve tested using Mousebytes, we’ve already identified similarities and differences between these mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease,” added Palmer. “This suggests when searching for Alzheimer’s disease drugs, data from MouseBytes can help in selecting the appropriate model for screening drugs to treat cognitive impairments.”

With freely accessible data, the researchers hope MouseBytes will continue to help find new insights into brain diseases and disorders including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia.

“Ninety per cent of the genes you have in the human brain, you also have in the mouse brain,” added Prado, a Robarts Research Institute, and Brain and Mind Institute scientist. “The hope is that by finding robust cognitive testing methods that can detect changes in the brain from Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or other mouse models, we can learn what’s happening in humans.”