Contact Information

Hassam Ansari

Communications Officer, BrainsCAN

Western University

hassam.ansari@uwo.ca

Q&A with Dr. Adrian Owen: Understanding consciousness

June 1, 2020 - BrainsCAN Communications

Consciousness is fundamental to being human. It allows us to understand the world around us.

In medicine, consciousness is typically tested by asking patients to respond to a command or a question. This simple test determines if someone is aware and responsive. But what happens in rare cases where patients are conscious with no physical ability to communicate and let others know they’re aware? It becomes a matter of life and death.

Dr. Adrian Owen is a Professor in Physiology and Pharmacology in the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, a Principal Investigator in the Brain and Mind Institute and a former Canada Excellence Research Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience and Imaging who studies disorders of consciousness.

Disorders of consciousness occur when someone is alive, but shows no signs of awareness. A car accident, blow to the head, or other severe incident involving the brain can cause a traumatic brain injury, leading to a disorder of consciousness.

Earlier this year, Dr. Owen conducted a London Public Library talk on disorders of consciousness and memory. This article is adapted from that talk.

What is consciousness?

Dr. Adrian Owen: In practical terms, consciousness is being aware of one’s surroundings. We are typically able to determine if someone is conscious when they appear to be awake and able to respond to a command, such as “squeeze my hand.” But what if a patient was conscious, aware, but simply unable to show us? The truth is, we’d never know if they were aware… that is, until quite recently.

What’s the difference between a vegetative state and a minimally conscious state?

AO: There are people all around the world who are thought of as being in a vegetative state. These people live in a bit of a twilight zone. I call it the gray zone – somewhere between life and death.

Vegetative state is commonly defined as ‘wakefulness without awareness.’ Patients in a vegetative state may appear to be awake, but will show no evidence of self-awareness, awareness of others, or awareness of their environment. These patients are typically able to breath on their own and maintain sleep and wake cycles.

Like vegetative patients, minimally conscious patients also usually have sleep and wake cycles, along with unassisted breathing, but these patients are able to show reproducible behaviour indicative of some level of self-awareness and awareness of the environment. However, they aren’t able to communicate reliably.

How do researchers tell if someone is conscious if that person can’t communicate?

AO: I was introduced to a gentleman in 2012 and he’d supposedly been in a vegetative state for 12 years. He was very typical of a vegetative state patient – he would open his eyes, spontaneously blink, fall asleep and snore. He would do all sorts of automatic things, but wouldn’t respond to any form of stimulation. When we asked him to blink, he wouldn’t do it; when we asked him to wiggle his toes, he wouldn’t do it. He had been like this for 12 years and this was the basis on which it was decided that he was in a completely vegetative state.

We decided to put this gentleman into a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scanner to get images of his brain at work.

We asked him to pretend he was playing tennis and when we did that, the scan showed a bright area of activity in his premotor cortex – a part of the brain that sets up sequences of arm movements. We see exactly the same brain activity when we ask healthy participants to do the same task in the scanner. When we asked him to relax, this area of activity in his premotor cortex disappeared.

These brain scans are what determined he wasn’t in a vegetative state at all. He was actually conscious, aware and trapped inside his body.

How are consciousness and memory connected?

AO: Consciousness and memory are closely related to one another. If you think about almost any experience that you have – any conscious experience – it’s really dependent on memory.

Some of the big questions we don’t understand about patients who appear to be in a vegetative state are: what is their experience of the world like, do they have new memories, and do they have memories from before their accident?

We conducted a study back in the UK in 2010. A patient had been in a motor vehicle accident five years earlier and was assumed to be in a vegetative state. When we asked him to imagine playing tennis, he could. So we asked him to do a second task; to think about moving from room to room in his house. This is what is referred to as ‘spatial navigation’ – what we do when we think about navigating through a familiar environment. When we asked the patient to do that, he produced a pattern of activity that was very similar to the pattern we see in healthy participants when we ask them to perform the same task.

So we had these two different tasks – imagining playing tennis and imagining moving around the house, and we thought, “let’s get this patient to do one of these tasks to convey a ‘yes’ and the other to convey a ‘no’.” This allowed him to answer simple yes and no questions just by changing the pattern of activity in his brain.

Using this very systematic method, we worked through a number of questions. We asked him whether he had a niece. This was to determine if he could still develop new memories because in fact, his sister had given birth to a daughter since his accident. To our delight, he correctly told us that he had a niece. The only way he could know that was if he were still taking note of the world around him and laying down new memories.

We asked him if he had ever been to the United States and he indicated that he hadn’t, which was again the correct answer, despite him having been to many other places around the world prior to his accident.

This series of yes and no tests showed us that he remembered events that took place before his accident and his memory was still intact. It also showed us that he was aware of events that took place after his accident and was able to lay down new memories.

Have these research findings resulted in a change in standards for evaluating patients in vegetative states?

AO: Everyone deserves an accurate diagnosis. For those we’re able to assess, I absolutely know we have impacted their lives by asking them questions about their situation.

I’m currently working on a BrainsCAN-HBHL research project with Stefanie Blain-Moraes, professor of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University to accurately predict the prognosis and long-term outcomes for unresponsive ICU patients. If successful, the results could transform care for patients suffering from severe brain injuries within Canada and abroad.

Our hope is that with increased and better access to technology, we will be able to bring these methods to more patients suffering from disorders of consciousness in Canada.

---

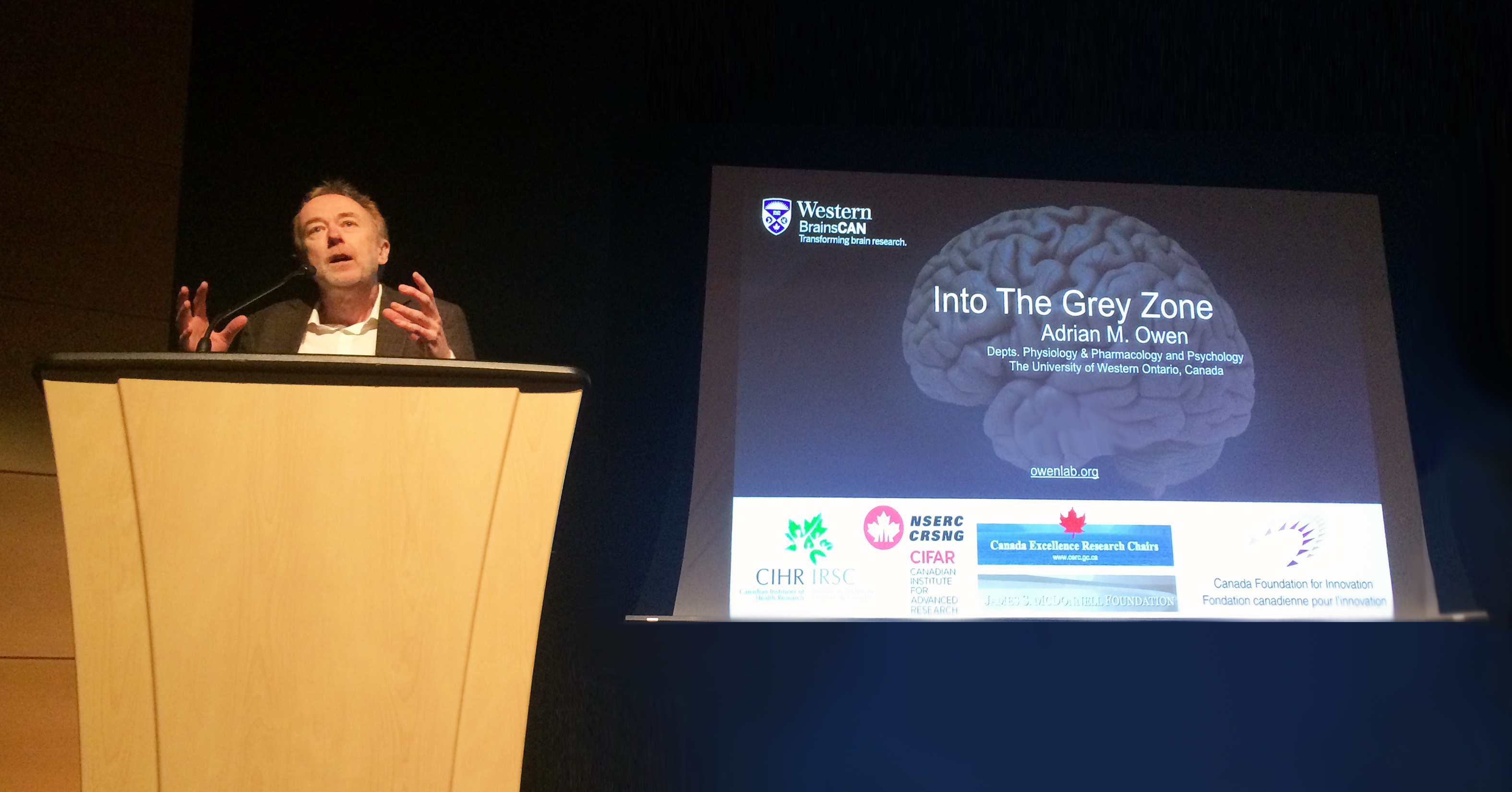

Dr. Adrian Owen speaking at the London Public Library event, Grey Matters – Conversations about Brain and Memory

Dr. Adrian Owen OBE is a former Canada Excellence Research Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience and Imaging, Professor in Physiology and Pharmacology in the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, a Principal Investigator in the Brain and Mind Institute, and founding Co-Scientific Director for Western’s BrainsCAN.